By Pawel Kowalik - Head of Product DENIC eG

Consecutive summary

NIS 2 is posing new challenges to the domain industry. Here are some thoughts on these and on possible approaches of assuring domain holder data accuracy from the perspective of the whole TLD market, including gTLDs and ccTLDs registries as well as registrars.

What to expect:

· What is NIS 2 all about?

· What are the requirements for domain holder data accuracy?

· Why should we care?

· What are the challenges?

In the dynamic landscape of the domain industry, history seems to be repeating itself. Just as the seismic shifts brought about by GDPR (General Data Protection regulation) are beginning to settle, a new wave of legislation, NIS 2 (Directive on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union), is knocking at our doors. This time, the stakes are even higher as, for the first time ever, legislation explicitly refers to top-level domain registries and other entities involved in domain name registration, such as registrars and resellers.

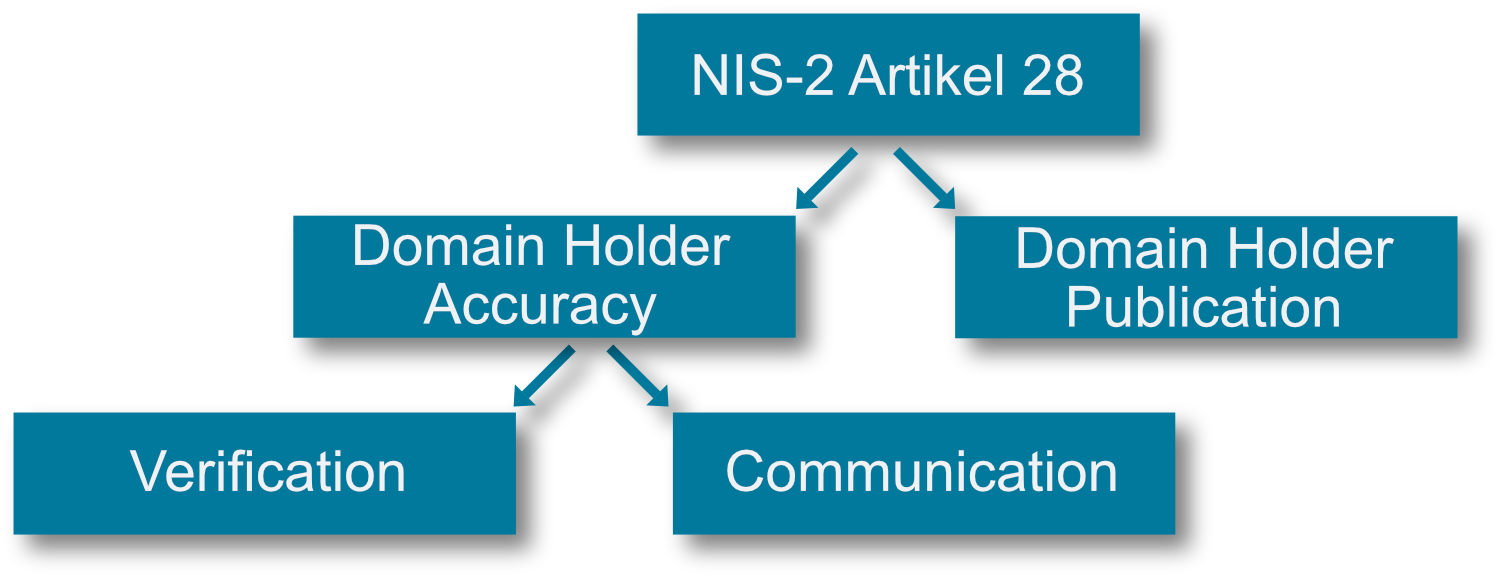

From the perspective of the domain industry, Article 28 is central to this regulatory overhaul. It introduces significant changes to the processes and data management practices among various industry players. The implications of these changes are profound and demand heightened cooperation and coordination across the board.

However, the path to compliance is full of challenges. Despite a firm EU deadline being set for October 2024, the transposition of NIS 2 into national law progresses at different pace across member states. Moreover, it cannot be guaranteed in any way that requirements will be similar or even compatible from one country to another, which adds another layer of complexity.

Both country code top-level domains (ccTLDs) and other industry stakeholders now face the daunting task of navigating this fragile environment. Article 28 of NIS 2 calls for enhanced cooperation between different players, but the exact mechanisms remain uncertain. It is sort of a moving target. As the domain industry grapples with these new regulations, the need for clear guidance and collaborative strategies has never been more critical.

What is it all about

Taking article 28 apart, one will notice two focal points of the legislation, each of which has a different level of complexity when it comes to implementation in the market.

The central issue is accuracy and completeness of registration data, whereby it is clearly defined which data elements must be collected.

Citing the most important elements of the Directive, TLD name registries and the entities providing domain name registration services shall:

· "... collect and maintain accurate and complete domain name registration data in a dedicated database with due diligence..."

· " ... the database of domain name registration data to contain the necessary information to identify and contact the holders of the domain names"

· "... have policies and procedures, including verification procedures, in place to ensure that the databases [...] include accurate and complete information."

The definition as such not being very precise, there is a lot of room for interpretation both by the member states when transposing the Directive into local law and by the parties involved. Without substantial coordination, Europe is running the risk of individual and potentially incompatible solutions being developed on all levels – starting from local law, through policies and processes up to technical protocols and implementations. Major fragmentation of the market would be the inevitable result.

The other part is related to access to the registration data by legitimate access seekers. Access seekers are asking for a greater standardisation of the processes and related definitions, so that their requests can be placed and are handled in the same way and within defined timelines by different parties in the ecosystem.

Domain holder data accuracy

In this text, I would like to share some thoughts on challenges and possible approaches of assuring domain holder data accuracy from the perspective of the whole TLD market, including gTLDs and ccTLDs registries as well as registrars.

These are based on the work conducted within the NIS 2 Working Group DENIC called to life in the beginning of 2023 with the goal to get a greater consensus between registry and registrars of different sizes and business models when it comes to NIS 2 implementation for the .de registry.

The group came up with a list of principles, which served as guidance for the solution design. The most relevant points included the following three:

· future-oriented, flexible and scalable – The group was convinced that after the initial implementation of NIS 2, there was going to remain a lot of room for interpretation and adjustments to be introduced later. Approaches which might look acceptable in the initial stage may become obsolete later when new technologies or processes become available and new threats emerge. This happened to GDPR and will inevitably also happen here. Therefore, the processes put in place should allow for adjustments to the method to verify the domain, which domains get verified and at which point in time, without having to re-invent the whole architecture anew.

· Ex post and ex ante verification possible – In the default setup, the process should be based on ex post verification, which would not block the reservation of the name in any way. Registrars who would like to conduct the verification before the registration – due to requirements of their own process or KYC obligations resulting from other fields of their activity, like telecommunications – should be enabled to do so and transmit the result prior to the registration in order to avoid the risk of potentially failed ex post verification and its negative consequences, like suspension or deletion of a domain name.

· Possible reusability of verification, even between TLDs – It is of primary importance that the same domain holder is not bothered with repeated verification if more than one domain is ordered, even if spread over a longer time period. The next level would be to assure that this will not happen, even if several TLDs are involved.

Why should we care?

One may ask why it is important at all to take care of the use case of one and the same registrant registering domains with more than one TLD. Looking at the situation exclusively from the point of view of a single TLD registry, especially from that of a ccTLD registry, no benefit in supporting this use case can be seen at the first glance.

The key to understanding the deeper issue is taking the registrar perspective – especially that from the user experience point of view.

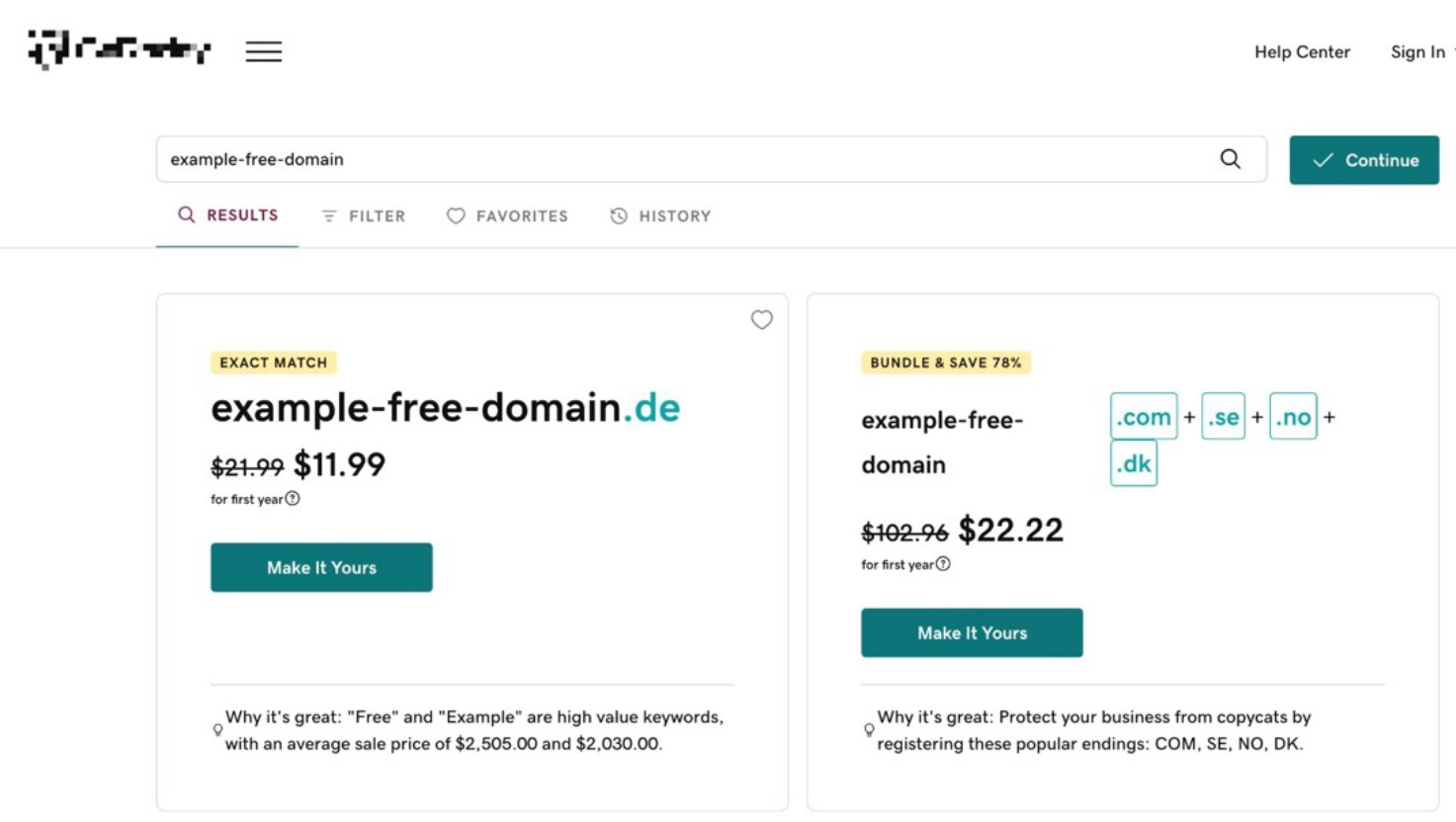

Let’s imagine a typical sales workflow of a registrar, offering a search for free domain names. A very common approach to maximise the basket value of the domain order would be a proposal comprising a fitting mix of TLDs with the same SLD string – a so-called domain bundle. Sometimes a price incentive is offered for the bundled package, sometimes it is enough to build a brand protection bundle with appropriate messaging to convince the registrant.

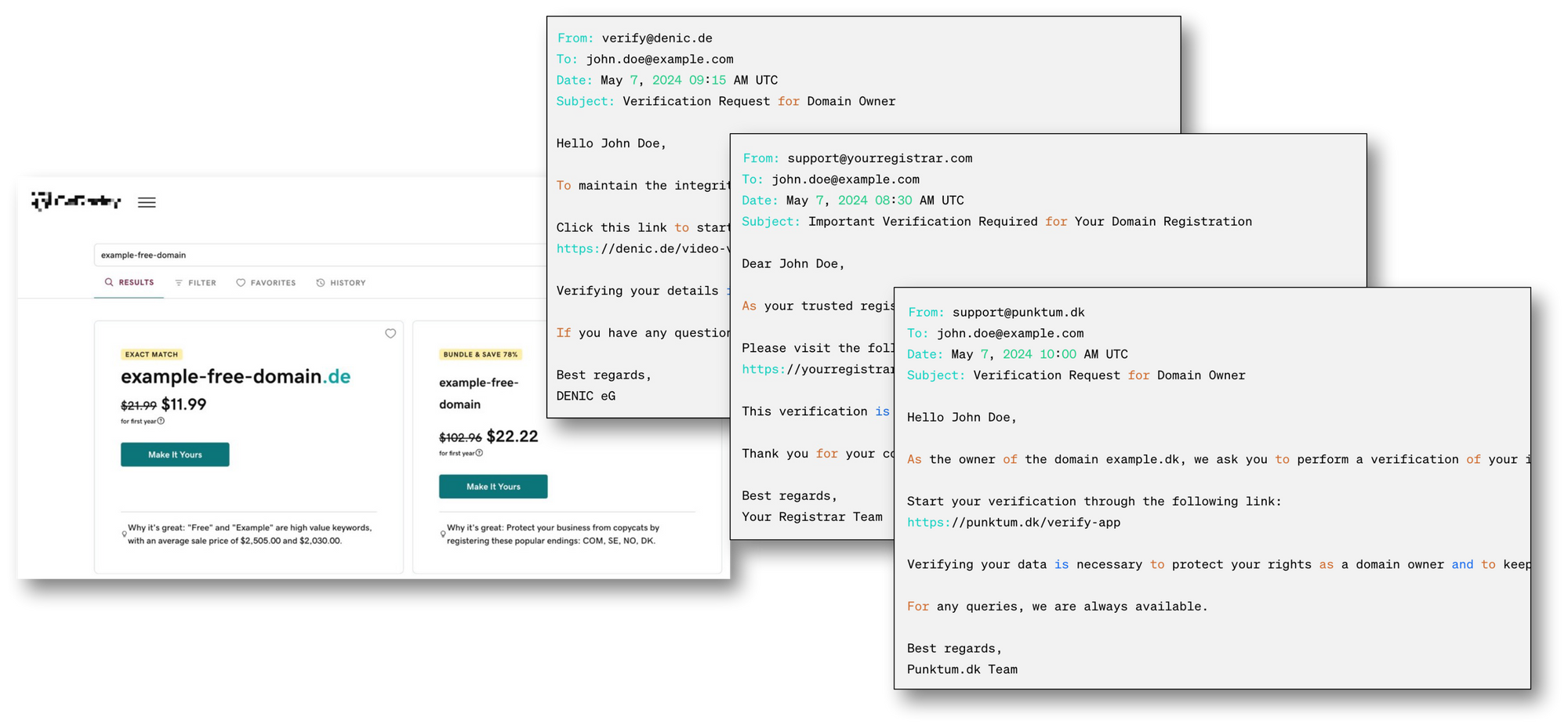

Following this scenario, assuming each of the purchased TLDs would apply their own unique process for verification, it is very likely that the registrant would be confronted with a series of requests from different parties asking to complete the verification. In some cases it would be a registry initiating the communication – often an entity the registrant never heard of. In some cases, it would be a registrar, just because so-called thin TLDs were concerned that cannot provide any of the data necessary to conduct the verification. The processes would also differ between the parties – sometimes the registrant would be asked to go to a website and complete the process, sometime to download an application. It might even happen that two registries use the same verification method. But because they do not know about each other's processes, the registrant would be asked to go through the very same steps twice. This is far from a good user experience.

Also the likelihood of the verification process to be completed would decrease, the more variations of the process the registrant would face. Due to continued threats coming from phishing, users are increasingly distrustful of e-mails coming from unknown parties asking to click on a link or download an application. This will happen even more as soon as the NIS 2 processes get established and bad actors start to harvest also on this kind of communication with their phishing attempts.

Survey data of DENIC registrars show that a registrar has 15 to 25 percent of domain registrants with more than one TLD, 40 percent of these domain holders with 3+ TLDs.

Assuming each of those registrants would be verified separately for each TLD, this would translate to up to 45 percent more verifications being performed.

Assuming each of those registrants would be verified separately for each TLD, this would translate to up to 45 percent more verifications being performed.

The problems

Yes, there are few:

· It’s a burden for all parties involved

· It's an additional cost with no value created

· It’s miserable UX

Not addressing these problems appropriately, will have consequences: Domains will be lost on the way. This will be due either to registrars being more reluctant to sell bundles or to make upsell offers, or to verifications not being completed by the registrant and consequently domains being removed from the zone or even deleted.

How?

Having the problem defined, there are two questions that need to be answered when looking for a workable solution. The first is how to conduct the verification and the second is which party is best suited to do it.

Let’s focus on the first question.

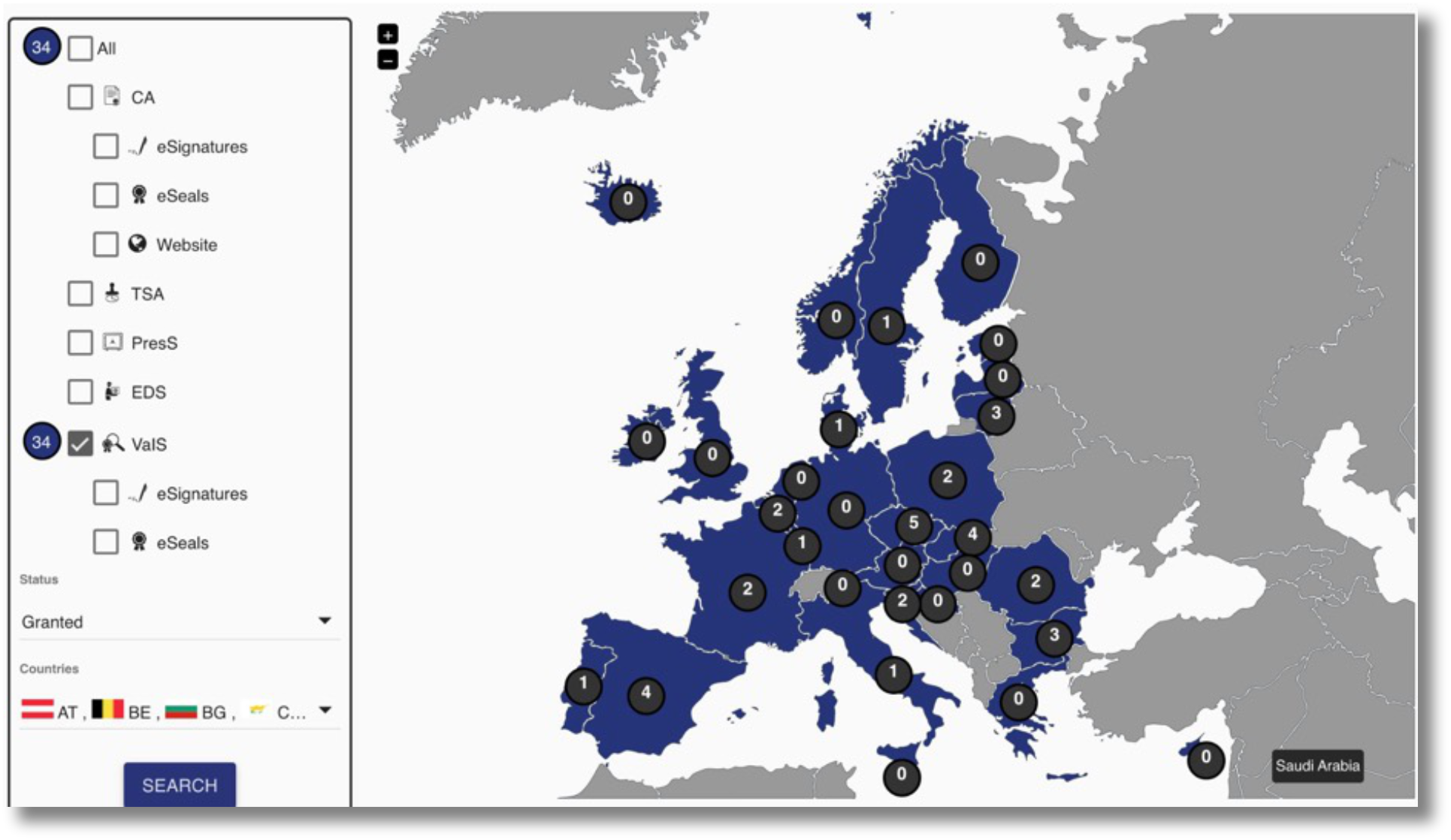

With an EU-centric view on the problem, one may think that eID and the eIDAS framework would offer a valid answer. Unfortunately, reality is not that bright.

First, not each EU country offers a system which can be used for this purpose cross-border. Some countries limit access to their eID nodes to the public sector, excluding the private sector. Finally, user adoption, the decisive success factor of the process, also differs widely between member states.

With eIDAS 2 and EUID Wallet, things might change. But the implementation timeline for each member state to establish the wallet infrastructure ending in 2025 plus the time needed for the solution to achieve an adoption rate worth mentioning does by no means fit the timeline of the NIS 2 implementation.

For DENIC, the answer whether eID is a viable solution was pretty simple. German eID adoption rate is very low, so that the solution would not fulfil its purpose for 89% of the registrants. Moreover, with registrants coming from over 230 countries, a prominent portion of them from non-EU countries, it was quite obvious that more verification methods are needed.

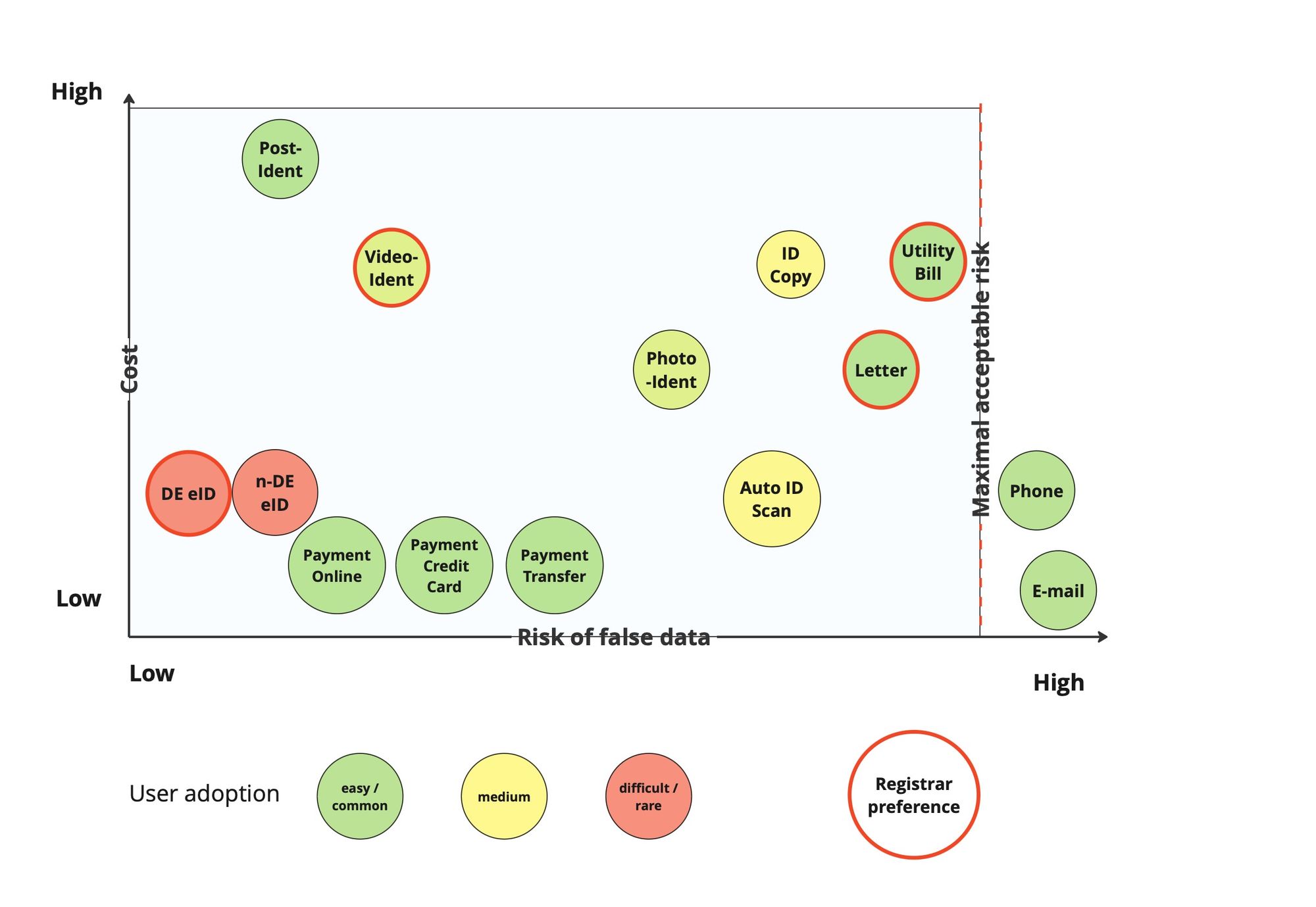

The approach DENIC discussed with the registrars took into account 3 dimensions:

· the level of assurance of a given method – in other words which risk level is acceptable regarding false data coming from a verification process

· cost

· user adoption

As a result, a wide set of methods has been defined, which allows a great level of flexibility in verifying the registrant when it comes to the methods available in the respective country and the evidence the registrant is able to present.

The approach offers a possibility to adjust with time if the legislation changes or the risk assessment of the methods differs over time. In that case, the registry just needs to adjust the list of allowed verification methods without changing the general model of operation.

Who?

Answering this question is not as obvious as it seems. And it was not an obvious or easy discussion within the Working Group at DENIC either. At the beginning, positions were quite far apart. Registrars rather looked at the registry, expecting it to solve the problem and at best leave registrars completely out of it. The registry on the other hand, was concerned about processes to be too much concentrated, about changes in established communication flows and the related shifts in the relationships between registry, registrars and domain holders. Only when taking a deeper look at the consequences and opportunities of the different models a unified view emerged.

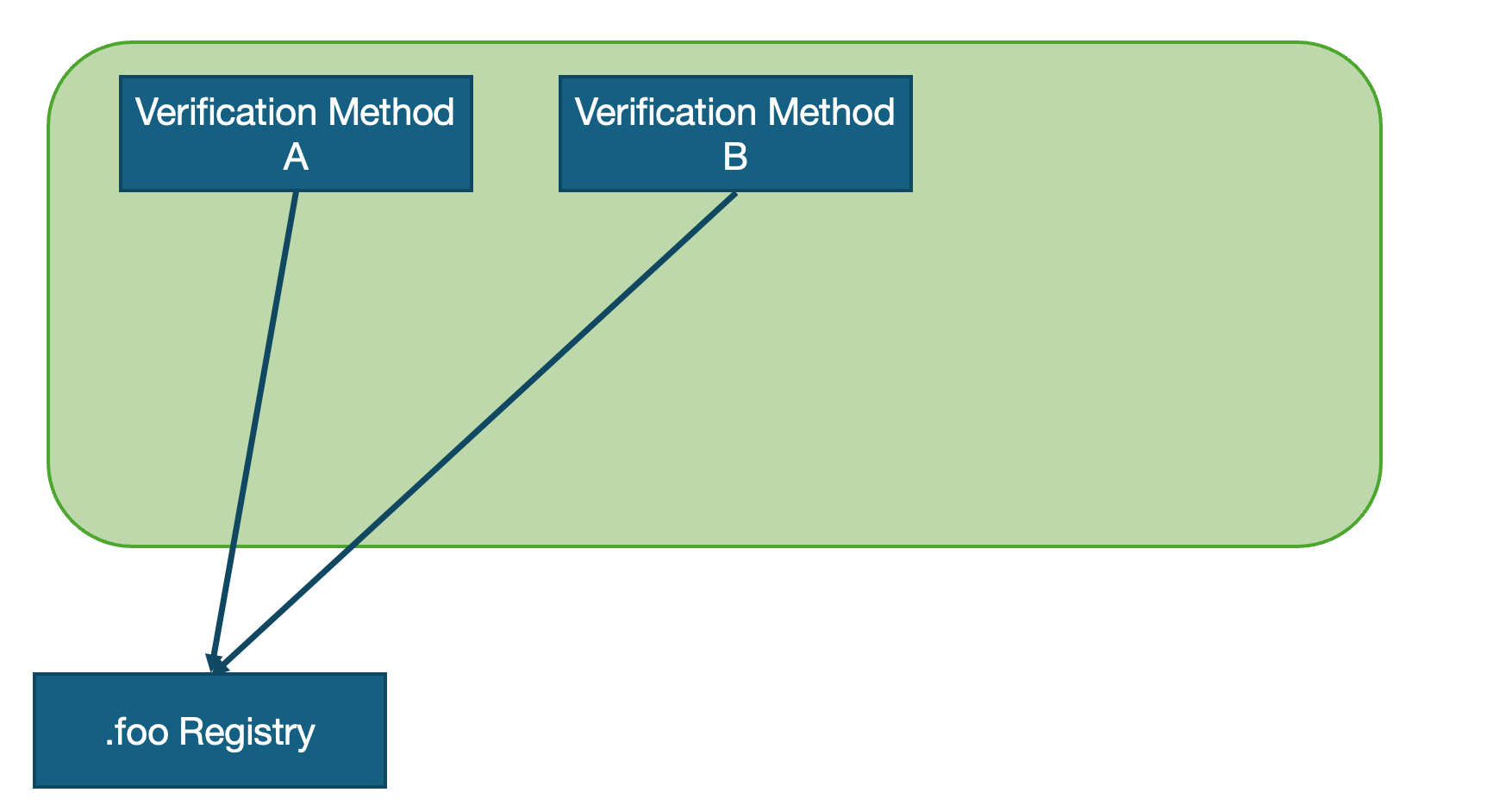

To get this understanding, one first needs to take a look at the simplified model, which is applicable first of all to ccTLD markets, where the registry primarily concentrates on a domestic market and serves mostly users from one country.

In this view, the registry serving only this one market can focus on few widely adopted verification methods applied in this market and can design its processes around it.

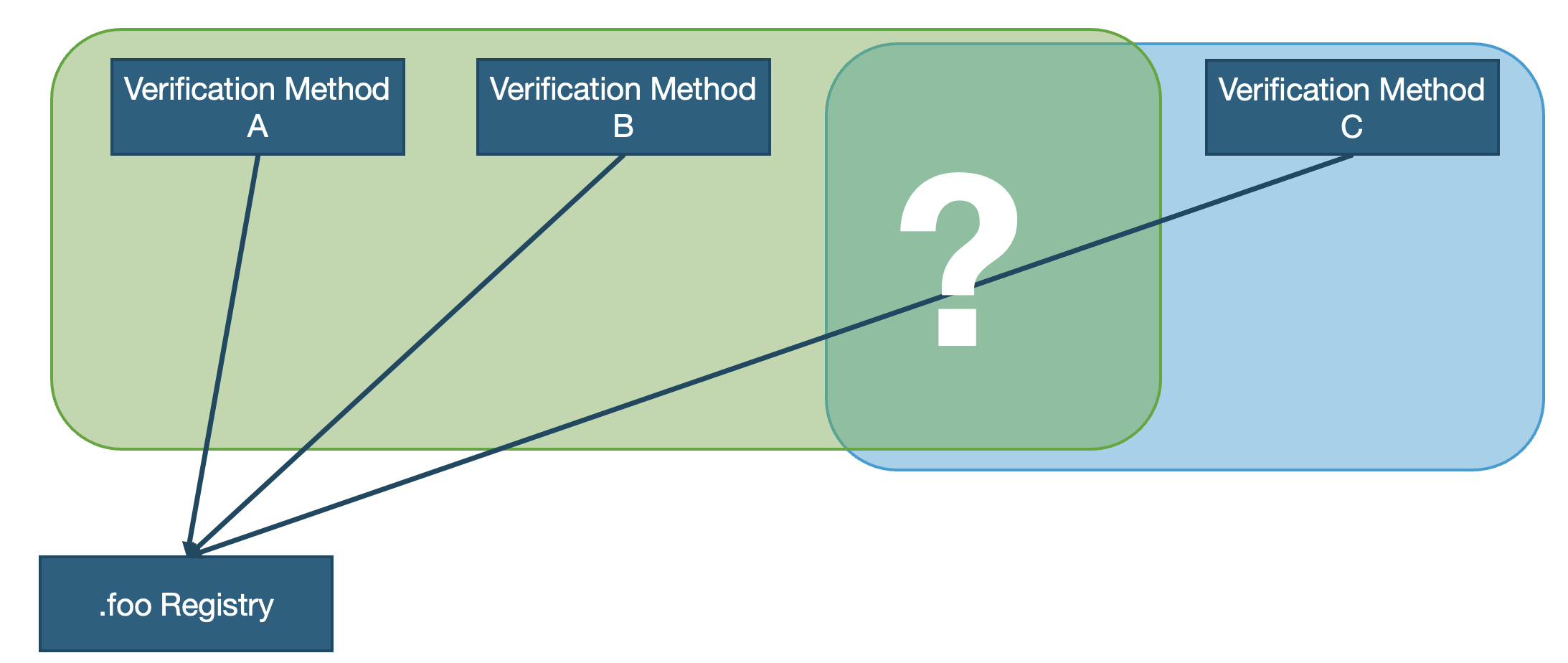

The situation gets a bit more complex when the TLD becomes available in other markets, thus allowing cross-border registrations. Some ccTLDs, especially in the EU make their respective registrations available to all other EU countries. As mentioned before, even within this narrow scope, where a lot of effort is put into making digital services work across the borders, there are no standardised solutions yet that would cover all cases.

Things get even more complicated if the TLD does not limit registration at all. In rare cases, however, the registry would be able to cover all possible verification methods for all countries worldwide. For a ccTLD registry, it would hardly be possible and surely not economically viable to support the domain holders in all countries, including local language and time zone.

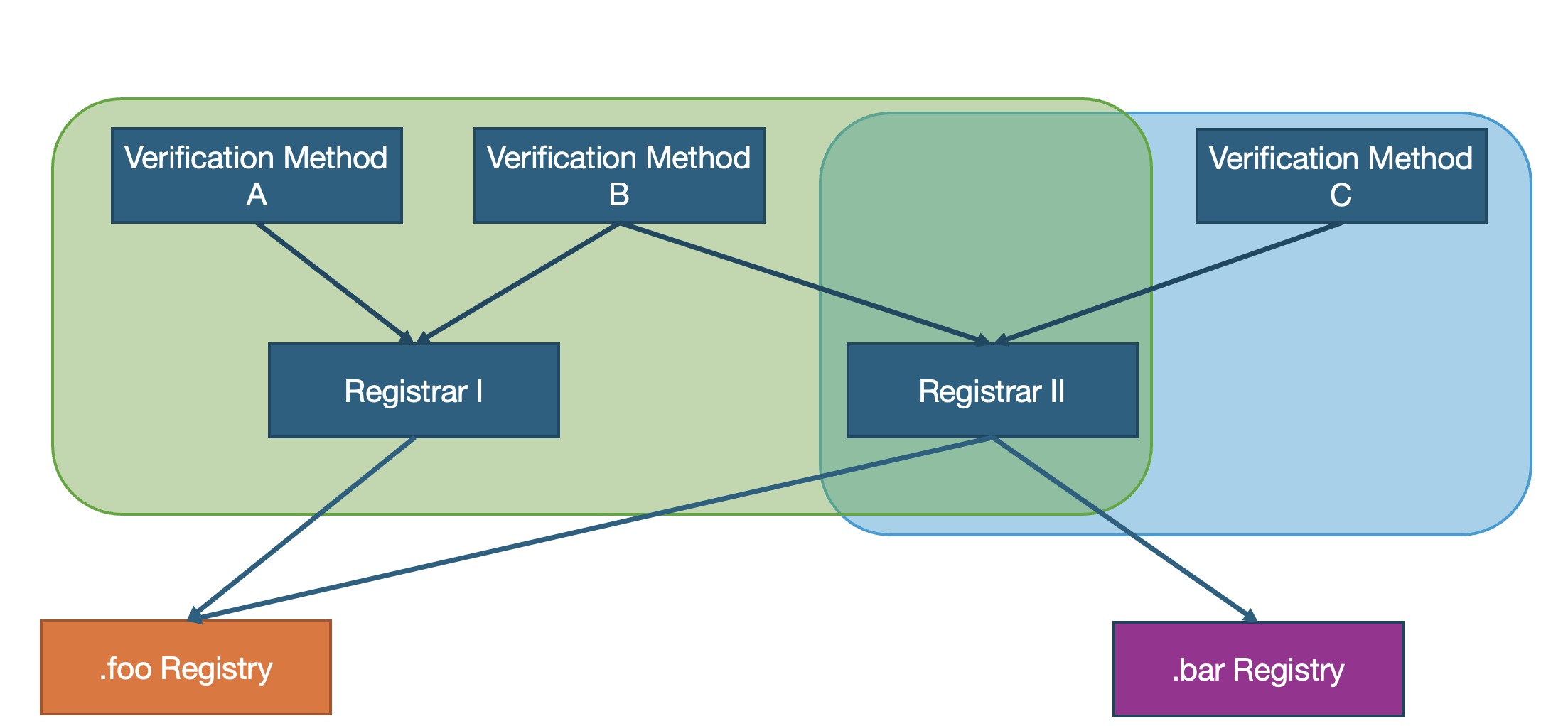

Verification requires close interaction with the domain holder and good knowledge and alignment with the target markets. This is the role typically assumed by the registrars in the R-R-R model. This solution also seems to be a valid answer to the question about the party best matched to conduct the verification process.

This approach offers also other additional benefits. The first being that the registrars actually have more data at hand which makes it possible to conduct a verification. Most of them, at least those directly offering services to the domain holders, possess also data related to the payment process, which in many cases would be conducted with a provider who already carries out verifications. In many cases, banks for example are required by law to conduct KYC (Know Your Customer) processes. So, if the data used for payments matches the domain registration data, this may already account for a successful verification.

The second benefit is that with this solution registrars can actually address the verification reusability problem mentioned before. If a registrar performs the verification for a domain holder for one registry, it may reuse this information when interacting with another registry about the same registrant.

How to get high reusability of verification?

In order to achieve high convergence and reusability of the verification, the TLDs would need to align to similar rules, without those having to be the same for all of them:

· Allow/Let the registrar do the verification– this will enable reusability

· Keep the verification data with the registrars, so they can reuse them – even if the registry will decide to take over the process, it is important for registrars to receive the verification result

· Keep the list of allowed methods and evidence open and generic – allow also manual or analogous processes – the wider the list, the more likely it is that another registry is able to match and accept an already existing verification

· Do not bind the process to a certain provider or solution – as much useful it could be to streamline the implementation, it would at the same time narrow down the opportunities for the registrars to offer good user experience or to use the alternative verified data they already posses

· Accept also verifications from the past, which is also common case for multi-TLD setups. This means if a registrar has already verified a client in the context of a domain registration with any ending, the verification will be accepted also for a later registration request from the same client for another TLD ending.

· Accept equivalent methods from other markets and registries (provided the information is returned to the registrar) – it would be the ultimate enabler for reusability if the policies would allow verification to be performed according to compatible policies of other registries.

Do not reinvent the wheel

The requirements introduced by NIS 2 are not completely new to the domain name industry. For gTLDs, some of the rules have been in place for quite some time, imposed by ICANN policies. Some ccTLDs, too, were already introducing processes to verify domain holder data before NIS 2 entered the stage.

From this perspective, it is very important for the registries implementing NIS 2 to take a look at these existing processes and, if compatible with their local policy situation, apply them in the same or a similar way to limit market fragmentation.

Some of the processes worth to be mentioned at this point are:

· E-mail verification process like for gTLDs

· Yearly data reminder through registrars (like ICANN RDRP)

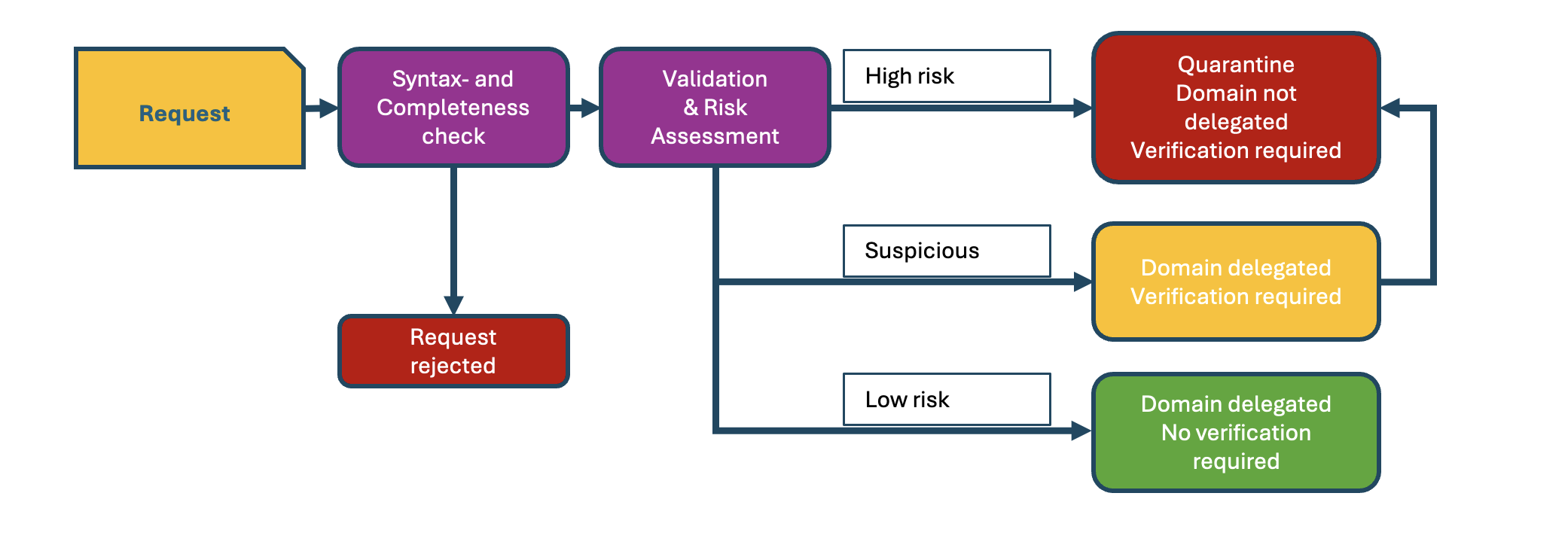

Model solutions also exist for the verification process as such, with risk assessment and traffic light system with optional elements of deferred delegation.

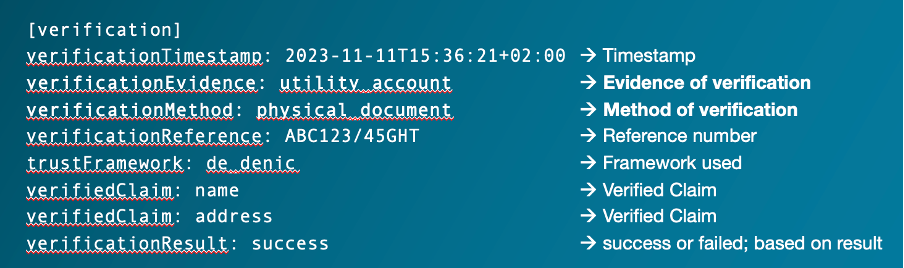

Moreover, even though NIS 2 as such still is too fresh to have established standards, there are numerous standards that can be reused when designing technical solutions. Especially in the realm of digital identities, impressive progress has been made over the last year regarding standardisation. This progress was strengthened by the eIDAS 2 and EUID Wallet efforts, which are based on OpenID Connect for Identity Assurance specifications. Even if, as mentioned before, it is too early to fully base verification processes on eID solutions, it is worthwhile to take a look at those specifications, methodologies, classifications and ontologies. Possibly, they can very well be applied by TLD registries, too.

Initiatives around CENTR

The CENTR community is very committed to finding possible alignments for the implementation of NIS 2 and the verification processes. Even though the member states are still in different stages of the transposition into local law, ccTLDs are discussing and preparing themselves for the changes.

There are several initiatives designed to increase convergence in the market:

· RANT Verification –led by DNS Belgium, with the goal to describe the generic process around registrant verification, define possible policy choices, document already existing approaches by different TLDs

· NISFITS – led by DENIC and NIC.at, with the goal to build a toolbox of technical approaches to model use cases around NIS 2 (EPP extensions, RDAP extensions, list of identifiers etc.)

· Adress checker – led by DENIC – a collaborative work to have the best possible address validation software module for all countries

Summary

NIS 2 may still appear to be a moving target to many players in the domain industry. Convergence is not easy and requires effort and readiness to cooperate. In this article, we have presented some principles, we think important to be considered, such as a future-oriented, flexible and scalable solution for data verification, ex post and ex ante verification and reusability of verification data. We also recommend all parties to choose solutions that are compatible with each other and ensure a good user experience. This also means allowing a wide range of methods and evidence – and above all intensive cross-border collaboration.

The approaches presented in this article offer no guarantee to success, but surely increase the chances of reducing fragmentation of emerging solutions. This is the chance we should all embrace to introduce NIS 2 responsibly in our markets.

This presentation was firstly conducted during Nordic Domain Days in May’24 and also in a limited scope as part of the panel discussion at the Registry Operations Workshop